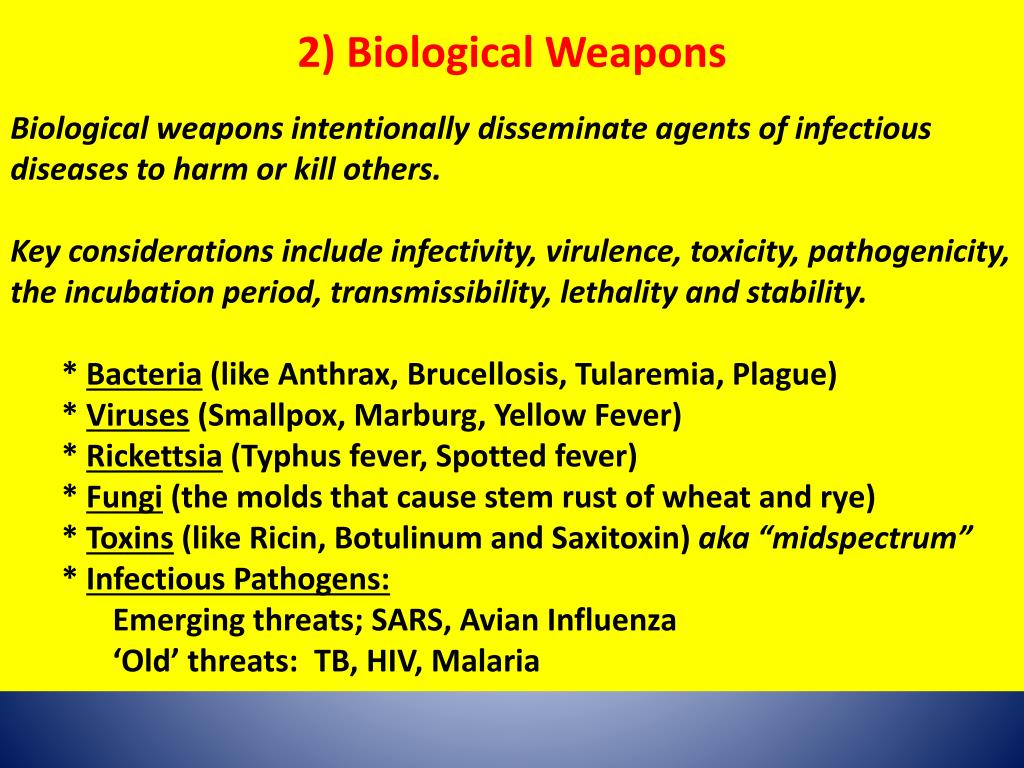

Regardless, most bio-security experts acknowledge that the potential of an attack should not be ignored. For example, the technical difficulties in aerosolizing a disease agent and dispersing it accurately and widely while maintaining its virulence are immense. Other defense experts and scientists insist that the possibility of any attack, especially a large-scale one, is small, given the immense challenges to cultivating, weaponizing, and deploying biological agents. Director of National Intelligence Mike McConnell revealed that, of all weapons of mass destruction, biological weapons were his personal greatest worry (McConnell, 2008). Office of the Director of National Intelligence and the National Intelligence Council stated in 2008 that bio-terrorism is more likely than nuclear terrorism. How Likely Is a Biological Attack to Happen?Įxpert opinions differ on the plausibility of a biological attack. The draft Model State Emergency Health Powers Act of 2001, which is a document designed to guide legislative bodies as they draft laws regarding public health emergencies, has defined bio-terrorism as “the intentional use of any microorganism, virus, infectious substance, or biological product that may be engineered due to biotechnology, or any naturally occurring or bioengineered component of any such microorganism, virus, infectious substance, or biological product, to cause death, disease, or other biological malfunction in a human, an animal, a plant, or another living organism in order to influence the conduct of government or to intimidate or coerce a civilian population.” Biological warfare and bio-terrorism are often used interchangeably, but bio-terrorism usually refers to acts committed by a sub-national entity, rather than a country. Many bio-weapon disease threats, however, lack a corresponding vaccine, and for those that do, significant challenges exist to their successful use in an emergency. Licensed vaccines are currently available for a few threats, such as anthrax and smallpox, and research is underway to develop and produce vaccines for other threats, such as tularemia, Ebola virus, and Marburg virus. Note that chemical weapons, such as those involving nonbiological substances such as chlorine gas, are not included.)Įffective vaccines would likely protect lives and limit disease spread in a biological weapons emergency. (This from the CDC lists all Category A, B, and C agents. Category C agents include emerging disease agents that could be engineered for mass dissemination in the future, such as Nipah virus. These include brucellosis, glanders, Q fever, ricin toxin, typhus fever, and other agents. These disease agents exist in nature (except for smallpox, which has been eradicated in the wild), but they could be manipulated to make them more dangerous.Ĭategory B agents are moderately easy to disseminate and result in low mortality. These are anthrax, botulism (via botulinum toxin, which is not passable from person to person), plague, smallpox, tularemia, and a collection of viruses that cause hemorrhagic fevers, such as Ebola, Marburg, Lassa, and Machupo.

Category A agents are the highest priority, and these are disease agents that pose a risk to national security because they can be transmitted from person to person, lead to high mortality, and/or have a high potential to cause social disruption. Public health authorities have developed a system to prioritize biological agents according to their risk to national security. government agencies are involved in planning responses to potential biological attacks.īio-weapon threats could include the deliberate release by attackers of an agent that causes one or more of various diseases. Biological attacks, however, have occurred in the past, one as recently as 2001. And indeed, the possibility of such an attack may be very remote. A biological attack by terrorists or a national power may seem more like a plot element in an action film than a realistic threat.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)